Looking at Public Sculpture in Dublin

The life of a city and the phases of its history are recorded in its public sculpture. A city would be incomplete without it. In the case of a capital city, national commemoration of a historic nature will also be evident in its public sculpture collection. Tourists, travellers to cities other than their own, tend to notice such public sculpture and in some cases it even forms a significant part of their itinerary. However, in our own city where we live, familiarity and the demands of normal daily life ensure that public sculpture is largely ignored by the local populace. Sculpture Dublin has as its mission the reintegration of these art works into our lives, establishing an enhanced engagement with the city by reasserting the visibility of its public sculpture.

What is public sculpture?

Public sculpture is often defined as being a portrait statue on a public street. Jim Larkin (1978, Oisín Kelly) (1) on O’Connell Street might be deemed a typical example. But this is to limit what is a diverse art form that manifests itself in many different ways and is found in a variety of locations. Public sculpture can take the form of something we recognise in the world around us or it can be form for its own sake, an abstract shape that does not reflect anything with which we are familiar in the real world. Its placing is not restricted to streets. It is also found in parks and in the grounds of or attached to the façades of public buildings. Nor is public sculpture only located in the great outdoors. There is sculpture in the city’s museums, in churches, in institutions and corporate buildings. This is a form of art that is used to commemorate particular individuals/events and/or to enhance specific locations. Think of the city as an open air museum, where sculpture enlivens and defines the spaces, educates and informs the viewers, engages and delights and sometime even confounds us – but hopefully always sets us thinking.

What are the beginnings of public sculpture in Dublin?

Public sculpture has its legacy in the ancient world and, in its portrait statue form, is not much different today. It is first seen in public spaces in Dublin in the eighteenth century. Dublin was then the second city of the British Empire and as such it was inevitable that statues of British kings were commissioned for its centre – an equestrian statue of William III for College Green (1701, Grinling Gibbons) (2); George I for Essex Bridge (1722, John van Nost, the elder) (3); George II for St Stephen’s Green (1758, John van Nost, the younger) (4). These were joined in the early nineteenth century by further imperial commemorations – colossal monuments of soldier heroes: Nelson (1808, Sackville Street, Thomas Kirk) (5) and Wellington (1822/56, Phoenix Park, Farrell, Kirk & Hogan) (6). The commanding presence of these monuments in the city, all five of them impressive in their scale, encouraged a clamour for statues depicting Irish heroes on the streets of Dublin – as a result of which, just after the mid-century, Thomas Moore (1857, Christopher Moore) (7), Oliver Goldsmith, Edmund Burke and Henry Grattan (1864, 1868, 1876, John Henry Foley) (8, 9, 10) found their way into the city in the area around Trinity College. This was the beginning of a half century when the commissioning of nationalist and imperial commemorations would alternate with one another for the public spaces, until the gaining of Independence when controversy over the presence of the latter saw most of them removed or destroyed.

What was the outcome of the statue controversy in Dublin?

If public portrait sculpture has its legacy in the ancient world, so too does its accompanying controversy. There was as much public dispute about monuments in ancient Greece, as there was in Ireland in the early twentieth century and as there is across the world today. Public portrait sculpture is inherently problematic. It was, and continues to be, rare that people are in agreement about who should be portrayed in our public spaces – about who merits being put on a pedestal and, of those already in place, who should remain there. In the aftermath of the gaining of Independence in Ireland Imperial statues were a target, violated in different ways before being blown up or removed from their locations. Over a period of nearly 40 years, between 1928 and 1966, the equestrian William III was first and the Nelson column last to disappear from the streets of Dublin. Three of the statues that were formerly in the city are now in England: George I (11) is at the entrance to the Barber Institute in Birmingham; the Earl of Carlisle (1870) (12) and the equestrian Viscount Gough (1880) (13), both the work of Foley and formerly in the Phoenix Park, are now in a private collection in Northumberland. The elaborate, overblown monument to Queen Victoria (1908, John Hughes) (14), formerly in the grounds of Leinster House, was dismantled in 1948 and removed to storage. The seated portrait of the Queen is now in Sydney, Australia (15), while the accompanying sculptures from the monument are displayed in Leinster House, Dublin Castle and in the formal garden at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham (IMMA) (16).

What is the range of public sculpture in Dublin today?

Public sculpture in Dublin today takes many forms and is often contextualised. The sculptor in his/her design must have consideration for the architectural and natural environment in which the work will be located. It may also be that the work will have a particular association with the chosen site. Statues and busts from the nineteenth century, representing mostly political and literary figures, were joined by further such commemorative portraits in the twentieth century, examples of which are James Connolly (1996, Beresford Place, Éamonn O’Doherty) (17), on the spot where Connolly often addressed political gatherings, and James Joyce (1990, North Earl Street, Marjorie Fitzgibbon) (18), whose statue could be located almost anywhere in Dublin, as he owns the city through Ulysses. Over time, with the advent of new forms of celebrity, popular culture became manifest in statues of Phil Lynott (2005, Paul Daly) (19), erected in Harry Street alongside the pub where he once played, and Luke Kelly (2019, Vera Klute) (20), whose colossal head is located in Sheriff Street, near where the singer was born and raised.

But it’s not all portrait statues. A sculpture symposium held to mark the Dublin Millenium celebrations in 1988 introduced new types of sculpture to the city beyond portrait imagery, several of which mark specific locations: Meeting Place (Lower Liffey Street, Jackie McKenna) (21), depicts two women who are resting on a bench mid shopping in the middle of a shopping area; Liberty Bell (St. Patrick’s Park, Vivienne Roche) (22), the very title of which echoes its location – in the Liberties alongside the Cathedral; Báite (Essex Quay, Betty Maguire) (23), a beached Viking ship incorporating seating on which to remember times past or simply wait for the bus!

Abstract work made its way into the public spaces in Dublin in the 1970s. Colourful bold steel forms are found in the forecourt of the former Bank of Ireland on Baggot Street (Reflections, 1975, Michael Bulfin (24); Red Cardinal, 1978, John Burke (25)). Simple forms in stone are integral to Sean Moore Park in Sandymount (An Gallán Gréine ‘Sun Stone’, 1983, Cliodna Cussen) (26); and a sweeping wood form makes a bold statement on Wood Quay outside the Civic Offices (Wood Quay, 1994, Michael Warren) (27). Abstract work is particularly present in the grounds of TCD. Arnaldo Pomodoro’s Sfera con Sfera (1980s) (28) outside Berkeley Library is complex and bewitching. Existing in multiple variations, the Sfera links us to sites of sculpture around the world, including the Vatican, the UN Headquarters in New York and Tel Aviv University. Most recently, Eva Rothschild’s A Double Rainbow (2020) (29) was commissioned for the new Central Bank building in the Docklands – the double rainbow, appropriately if not necessarily intentionally, symbolizing future success. Rothschild could not have known, when she was commissioned in 2019, just how eloquent the rainbow was to become the following year. Her colourful forms, at once spindly and monumental, are destined to be singularly present in their location without dominating the space.

New forms of sculpture are also evident in Dublin, notably outside the Hugh Lane Gallery, where Suzanne in her leather skirt walks day and night – rhythmically, hypnotically. Retaining links to tradition, this is a figure on a pedestal. But in reality this sculptural form is an animated LED work – far from traditional, very twenty-first century. The technique employed in Suzanne Walking in a Leather Skirt (2006) (30), allowed Julian Opie to achieve what has been an aim of sculptors over centuries – to animate a static figure.

How does a piece of public sculpture get to be erected in the city, who owns it and who is responsible for it?

These questions have different answers, dependent on the location of the work.

Ownership: In the case of institutions and corporate buildings, the sculptures are chosen, owned and maintained by the authorities of the particular organization. Sculptures located on the streets, in parks and in public buildings are owned and maintained by either Dublin City Council (DCC) or the Office of Public Works (OPW). The selection of work for these public spaces today is fully transparent – which can be witnessed in the commission briefs for Sculpture Dublin (on this website). A sculpture competition is held, a selection panel makes a short list from which a sculptor is ultimately selected. In the nineteenth century the public paid for many of the monuments that were erected. The Monument to Daniel O’Connell (1882, O’Connell Street, J.H. Foley) (31) was paid for by public subscription, with individual amounts donated published by name in the newspapers of the day. The extent to which people wanted to be involved is evident in the contribution of a ‘working man’ to the fund in 1862 – a penny for himself, his wife and each of his ten children. The system no longer requires that we put our hand in our pockets, but this does not make the work any less ours, and should not make us any less interested.

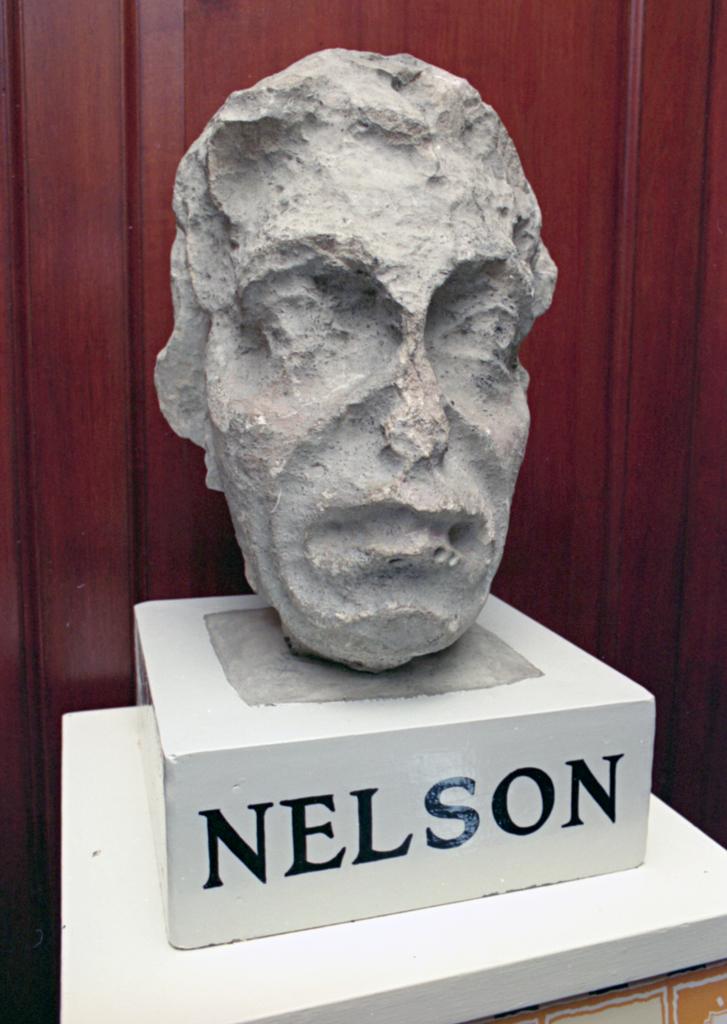

Maintenance: Public sculpture located outdoors requires protection from multiple sources –from the elements (weather), from pollution (birds and traffic), and, sadly, from vandalism (people). The ongoing maintenance of these works is costly. An example of long term damage can be seen in the head of Nelson (32), which is displayed in the Reading Room of Dublin City Library. Positioned atop the column on O’Connell Street for more than 150 years, the face was so weathered and lacking in definition when it fell, that it can no longer be recognised as a portrait of the man it is deemed to represent.

What is Temporary Work?

Sculpture has mostly been considered an art form that was intended to endure through time. The lasting quality of bronze and marble confirm this. Temporary work, a more recent aspect of public sculpture, will usually be made out of more contemporary materials and will either be ephemeral or will simply not be intended to remain in the location for which it was originally commissioned. An early example of this in Dublin was found on Leinster Lawn, where a monument cenotaph commemorating Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith by George Atkinson was erected in 1923 (33). Made of transient materials, as well as being politically contentious, the monument was replaced in 1950 by the Cenotaph obelisk by Raymond McGrath (34). At the other end of the century, in 1994, fibreglass toy soldiers, lifesize and brandishing rifles, appeared briefly on the streets of Temple Bar. Not a Bother (35) was Jeanette Doyle’s contribution to a street art symposium. The best known example of temporary work today is in London’s Trafalgar Square, where an empty plinth (the Fourth Plinth) (36) features a new work every year, work that subsequently makes its way to a different location. Sculpture Dublin has included in its programme a commission for such a temporary work to be located outside the City Hall on the empty plinth that once supported John Hogan’s statue of Daniel O’Connell (now inside the City Hall) (37). In November 2018 Dublin experienced the temporary display of a travelling sculpture, when The Hauntings Soldier (Martin Galbavy) (38) was exhibited in St. Stephen’s Green for three weeks. Made from scrap metal and commemorating the centenary of the end of World War I, the sculpture caught the public imagination, as much by way of the nature and purpose of the work, as by its short-lived presence in the city.

Is there a ‘best’ public sculpture in Dublin?

If there was a competition to find the ‘best’ public sculpture in Dublin, it is likely that almost all of the sculptures would get a tick. Someone somewhere would think a work unnoticed by others was the best. The ‘best’ is entirely subjective. Molly Malone (1988, Suffolk Street, Jeanne Rynhart) (39) appears to be the most popular sculpture in Dublin; the Daniel O’Connell Monument (40) is probably the finest. There is no ‘best’. But when choosing, it is important to consider both the sculpture and its context – to take into account how the sculpture works within its setting. Each member of the Sculpture Dublin steering group was invited to choose and comment on their favourite sculpture in the city. The responses have been incorporated into this website. We have laid our cards on the table and the variety in itself is revealing!

Concluding Comment

It has been suggested that monumental sculpture should represent a nation’s triumphs or its tragedies. The sculpture in the public spaces in Dublin, however, does not represent the whole of the country’s past. Sculptural indications of Ireland’s colonial history have largely been obliterated, as a result of which the city does not have the full range of monument types that might be expected in a capital city in the western world. The equestrian statue in particular is missing from the streets – missing, that is, until John Byrne decided to revive it in a commission for Ballymun in 2010. Misneach (Courage) (41) draws the past into the present. Deciding to model a horse and rider, Byrne chose the rider of the horse from the local community in Ballymun and the horse on which she is seated from Foley’s Gough statue (formerly in the Phoenix Park) (42), from which he made a cast. Byrne updated the equestrian statue for the twenty-first century.

Dublin is replete with sculptural works – sculptures that represent national and local figures; sculptures that identify individual areas of the city; sculptures that are simply there for our enjoyment. The city is not only a place in which to work/shop, eat/drink, it is a place in which we should take time to wander, to enjoy the public spaces. The sculptures, which give a focus to those spaces, have been placed there for us. It’s time to be tourists in our own city, and if we haven’t already, to begin to get to know the sculptures. They reflect change over time – change as a result of historical and social developments local or national, as well as changing art forms and styles.

It is important to take time to look and when you think you have finished looking to look again. Look – to locate the Act of Catholic Emancipation on the O’Connell Monument (43). Look – to note the moment of creative reverie in the Goldsmith statue (44). Look – to see the green carnation held in the hand of Oscar Wilde (1997, Merrion Square, Danny Osborne) (45). Look – to recognise the uniform of a Volunteer (The Soldier, 1939, Blessington Street Park, Leo Broe) (46). Look – at individual words in Michael Biggs’s awe-inspiring lettering of the Proclamation text incised on a wall in Arbour Hill (1956) (47). Look – to be informed about Ireland’s early industrial progress in Gabriel Hayes’s relief sculptures on the façade of the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation (1942, Kildare Street) (48). Look – to see yourself reflected in the mirrored stainless steel spheres that form Eilis O’Connell’s Apples and Atoms (2013, TCD) (49). Look – to make your own addition to this list. Sculpture Dublin encourages you to LOOK!

—Paula Murphy,

Professor Emerita, School of Art History and Cultural Policy, University College Dublin, August 2020

Credits for images featured in this essay are available here.